I’m launching myself head first into a somewhat contentious and heated debate on Traditional vs Simplified Chinese Characters. (What can I say? I’m a giver.)

For those of you without a personal stake in the matter, the issue may seem a bit silly and perhaps, unnecessarily muddies the water in Mandarin Immersion schools and curriculum discussions. However, it is a rather important thing to consider and decide because even though they are both the written language for Chinese, they are different enough that someone who only reads Simplified may have difficulty reading Traditional (and vice versa).

What is the difference? Traditional vs Simplified Chinese

Traditional Chinese Characters are Chinese characters that do not contain the newly created characters or character substitutions performed after 1946 by the People’s Republic of China (PRC). These characters are used primarily in the Republic of China (ROC aka Taiwan), Hong Kong, Macau, and overseas Chinese in South Asia.

Simplified Chinese Characters are the standardized Chinese characters in use in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). In the 1950s, the PRC drastically simplified many Chinese characters on average by about half their strokes in order to promote literacy. (See, even Chinese people thought Chinese was hard to learn!) These characters are used primarily in the PRC, Singapore, and Malaysia.

Okokok. Those are pretty dry definitions and actually do little to help folks completely unfamiliar with Chinese characters which to be fair, likely all look the same to the illiterate.

After all, how does a person who has little to no first-hand experience decide if their kid should learn Traditional vs Simplified Chinese characters?

For those of you who see the rather intimidating block of text below, here’s the tl;dr:

If you do not have a particular preference, choose whatever will be more easily supported by your time, interest, resources, and abilities.

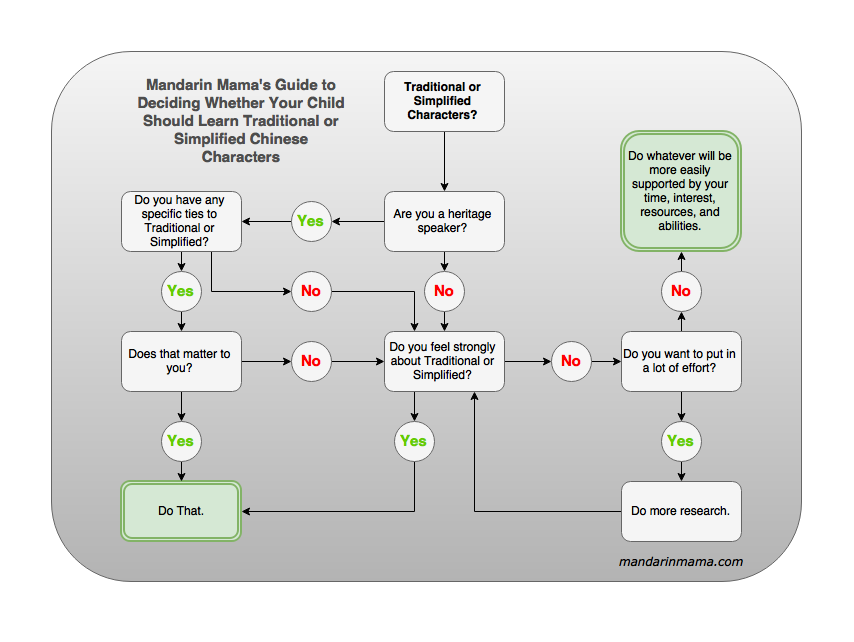

If you have just a little bit more time, I refer you to my Fancy Flowchart™ (aka: Mandarin Mama’s Guide to Deciding Whether Your Child Should Learn Traditional vs Simplified Chinese Characters) that should help 80% of you out there. As for the remaining 20%, let’s be real. No flowchart, no matter how amazing, would suffice. But fear not! There’s more info after the Fancy Flowchart™.

(As a side note, I am inordinately pleased with myself for creating this flow chart. It’s a sad but real thing that it took me HOURS to create. But I will forgive myself because most of that time was spent trying and discarding different free flow chart software both online and off. Now, if I can figure out how to make it Pinnable, I will win the internets for today.)

For those of you who do not know, there is a raging debate within the Chinese community about whether Traditional vs Simplified Chinese characters are better and why. Some of it is due to political ideology, some based on preference, and some based on practicality. If you are really curious, may I suggest to you this link.

It will be no surprise to many of you that I preferred Traditional Characters – and staunchly. However, as much as I personally prefer Traditional characters, that doesn’t necessarily follow that I think your child should learn Traditional. (Of course, it would benefit me if more folks chose Traditional because then there would be more materials easily available in the US, but that is an entirely different topic and not altogether germane to this particular discussion.)

In true fact, my opinion on what people should choose has changed greatly. I find that the further along I am on this journey of teaching my kids to be literate in Chinese, the more nuanced and pragmatic my opinion becomes.

When I was younger, I was told Mao butchered the Chinese language in order to pass along a Communist agenda. After all, why else would you take the “heart” out of “love” and truncate characters associated with goodness and virtue but leave whole all the characters associated with evil and disobedience?

(Incidentally, whether this is true or not, I’ll leave up to you to decide. But also know that many of the Simplified characters were changed to older or cursive forms of the characters, so it’s not as if Simplified characters were just made up out of whole cloth. There are rhymes and reasons to the simplification.)

In fact, I was so against Simplified due to this “Communist agenda” that I had at first, refused to allow Cookie Monster to go to one of his current Chinese teachers because she only taught Simplified. I didn’t want him learning to read and write Simplified Chinese. It seemed contrary to all that I had been taught and believed about the beauty of the Chinese language. Plus, I was worried that he would be confused learning both Simplified and Traditional characters – as well as prefer Simplified because it would seem easier.

And yet now, I can’t imagine Cookie Monster not attending class with this teacher. She is wonderful, kind, and fantastic. (I had initially been intimidated because she seemed super Tiger Mom and I was really worried Cookie Monster’s spirit would be crushed. I was so, so wrong.)

Cookie Monster has no problem recognizing the same Chinese character in both Traditional and Simplified. He just accepts that there are different ways to write the same word and rolls with it. I think that is a good way to go.

Here’s the thing: Language isn’t static – no matter how we may wish it.

After all, American English evolved from British English – which itself has evolved from Old and Middle English (which is nigh incomprehensible to us modern folks). Yes, the different spellings, phrases, and terminology aren’t as drastic as the differences between Simplified and Traditional, but you get the idea. My point is that they all still manage to be English and neither is Old English.

There will always be people who lament change to language. (Confer “literally” now also meaning “figuratively” and joining the dubious ranks of “cleave” being both itself and its antonym. Boggles the mind.) I am often one of those lamenters. But I also recognize that language is a living, breathing organism, constantly changing and morphing, depending less on the official definition and more so common use. So, if the common person is woefully ignorant, so thus changes the language.

And say you object to Simplified characters on an ideological basis (ie: Communism is bad, etc.). I get it. I do. However, you speak English, right? Americans, the English, and other English speaking countries have totally edited their history and language to erase the past and their colonial and genocidal tendencies. That has not led to my boycotting English.

Or perhaps you speak Spanish? Or Japanese? Or German? Or Russian? Or Arabic? I mean, seriously. If we’re going to argue against a written language based on bad shit that people speaking/reading/writing the language did (eg: mass genocide; fascism; you name it, a country’s done it), then quite frankly, we should just all start speaking Esperanto.

But I digress.

Anyhow, for the rest of this article (and really, any other articles about Traditional and Simplified characters), you will need a basic understanding of how a Chinese character is formed. I promise it’s relatively painless and quick. (I also blatantly copy/pasted from Wikipedia because laziness.)

Ok. Here are the basic types of Chinese characters and what they mean. If you want actual examples of characters, click through to their respective links.

- Pictograms – stylized drawings of the objects they represent (~600)

- Simple ideograms – express an abstract idea through an iconic form, including iconic modification of pictographic characters

- Compound ideographs – compounds of two or more pictographic or ideographic characters to suggest the meaning of the word to be represented

- Rebus (phonetic loan) characters – characters that are “borrowed” to write another homophonous or near-homophonous morpheme

- Phono-semantic compound characters – characters that are created by combining a rebus with a character that has a similar phonetic complement with a character that has an element of meaning (over 90% of characters)

If you are a language nerd like I am, you can find out more here (The last three are links to GuavaRama because quite frankly, she’s awesome and breaks things down in very simple terms. She is, after all, teaching her young children.):

1) How a Chinese character is formed.

2) Chinese character structure

4) How to write beautiful Chinese characters

Alright, enough preamble. (Good Lord, I babble.) Here then, are some more of my abbreviated thoughts on Traditional/Simplified characters. I am using bullet points because quite frankly, I’m tired and it’s far more concise and easier to visualize.

(A/N3: Much of this information would not be possible without the fruit of Mind Mannered and her careful research, summary, and references. Seriously, without them, my post would be mostly opinion, conjecture, and Wikipedia links. All of the academic references and a good portion of what follows comes from Mind Mannered’s summary as indicated in the references, but I also include many of my own points.)

Traditional Chinese Characters

1) Strengthens parsing semantic and phonetic information due to the way Traditional characters are structured and formed (see above). (1)

a) Provides more visual cues to support reading and helps facilitate learning and character recognition. (1)

i) Researchers have explained how this often helps young children recognize Traditional characters more easily than Simplified characters. (2, 3, 4, 5, 6)

b) Focuses more attention on the general principles of the written language, particularly how phonetics and semantic radicals are combined to make characters. (1)

i) Children perceive characters as being more similar based on how they sound vs how they look (3)

ii) Allows children to guess words based on context and combined phonetics/radicals.

iii) Follows more regular patterns (7)

iv) Research on language learning emphasizes how explicit, systematic instruction in the structure of the language is more helpful than incidental exposure and rote memorization (7)

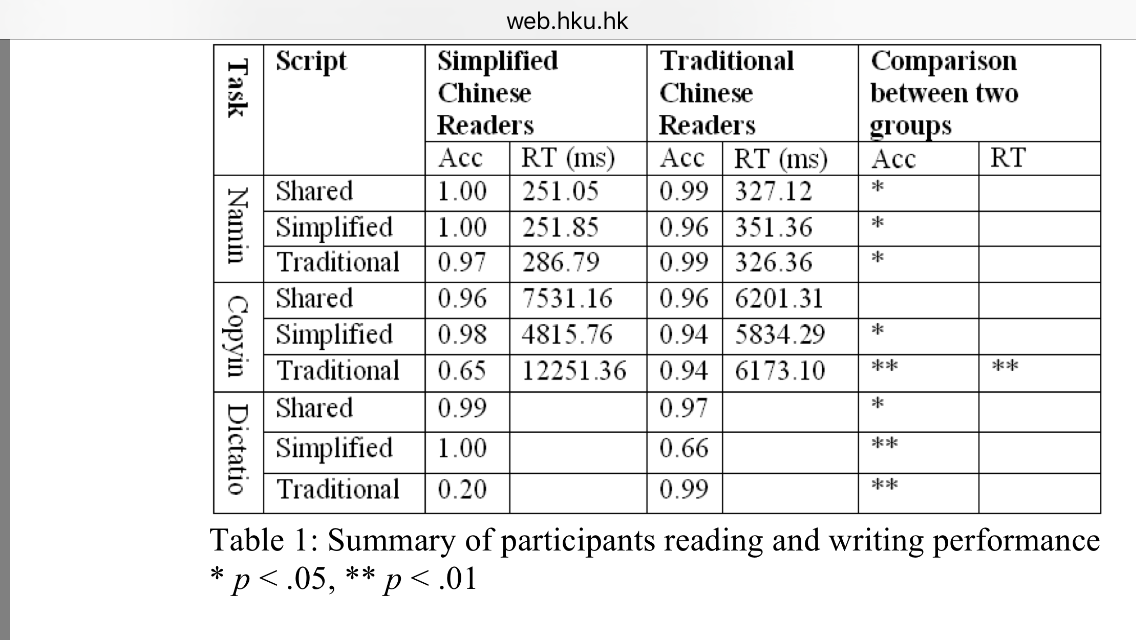

2) Easier transition to reading Simplified even without prior instruction (Table 1)

3) Harder to write

4) Even within the Traditional script, there have been adoptions of Simplified characters.

a) 台灣 (tai2 wan) instead of 臺灣 (irony: the “Tai” in Taiwan)

b) 画 (hua4) instead of 畫

c) 什 (she2) instead of 甚

5) Fewer resources in the US and harder to access materials unless you buy/ship from Taiwan/Hong Kong

a) No textbooks/curriculum adhering to Common Core

i) I can understand that unless a Mandarin Immersion school was formed specifically with the Traditional characters in mind, most MI schools may choose Simplified for this reason alone.

Simplified Chinese Characters

1) Strengthens visual and spatial relationship skills due to the way Simplified characters are structured and formed (see above). (1)

a) Provides fewer visual cues so requires more attention to detail when learning characters via rote memorization. (1)

i) Even with fewer visual cues, 1 billion Chinese people still manage to learn and be literate.

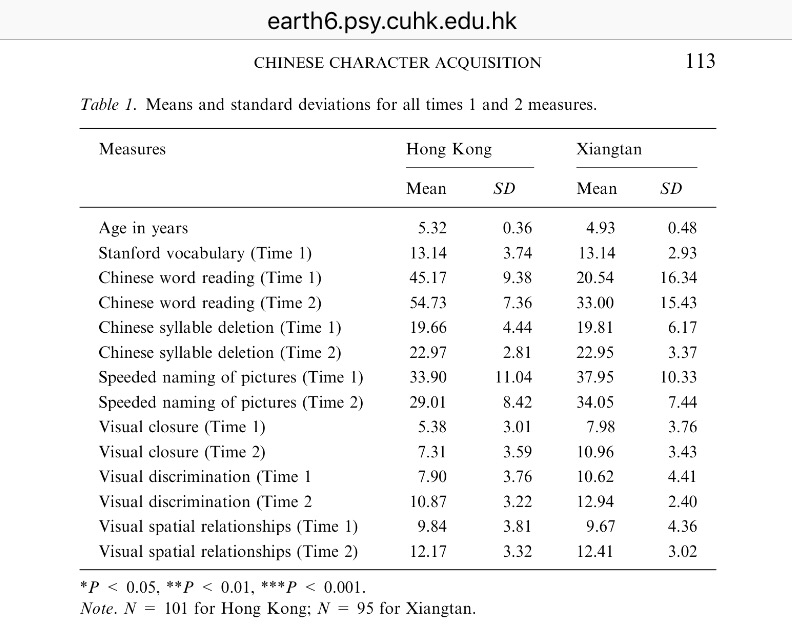

b) When controlled for reading ability, results showed that children learning Simplified characters demonstrated superior visual skills. (Table 2)

c) Children perceive characters as being more similar based on how they look vs how they sound (2)

2) Easier to write

3) Approximately 1 billion people use it

4) Lots of resources in the US due to the Chinese government, in conjunction with the Obama administration, actively encouraging US students to learn the language.

a) Common Core textbooks/curriculum are developed (although untested and many are in their first editions)

5) Harder time reading Traditional without prior instruction (Table 1)

a) However, I know plenty of people who have figured it out with great facility so I doubt it’s much of a hurdle.

6) Some character represents multiple words.

a) Context helps and I refer you again to 1 billion people who have figured it out. Plus, English has many homonyms and English speakers figure it out without much problem so even though I find it weird that Simplified Chinese has made many separate characters with the same pronunciation into the same character, I am confident that people can figure it out from context.

I know that this is far from all-encompassing, however, short of becoming a PhD in the subject (and I emphatically am not), I think this should suffice for most folks who have no preference (or clue) regarding Traditional or Simplified characters. And if not, well, Google is your friend. Also, the library.

And so, after this ridiculously long post, (and come on, when have my posts in this series been short?), I refer you again to what I said at the very start:

If you do not have a particular preference for Traditional vs Simplified Chinese, choose whatever will be more easily supported by your time, interest, resources, and abilities.

(See? I told you all you needed to do was read my Fancy Flowchart™.)

Thanks for sticking it through. If you’re still wanting more, I have included tables and references below. Many thanks, again, to Mind Mannered for her research and hard work. Your summaries cut down my research time significantly. Plus, your documents were so well executed!

Have a great weekend, everyone!

ETA: Again, my extreme and humble apologies to Mind Mannered. I would be furious and hurt if I were in her shoes. I was super lazy and an idiot and didn’t check your references to ensure that I wasn’t stealing proprietary work. I am very sorry for any and all distress I may have caused. Also, thanks to Mind Mannered, we have a lovely list of references to check out.

References

- Mind Mannered (2015). Research Highlights on Learning to Read and Write Chinese, private paper

- Seybolt, P. J., and Chiang, G.K.-K. (1979). Introduction. In P. J Seybolt & G. K.-K. Chiang (Eds.), Language reform in China: Documents and commentary (pp. 1–10). NY: M.E. Sharpe.

- Chen, M. J. and Yuen, C.-K. (1991). Effect of pinyin and script type on verbal processing: Comparisons of China, Taiwan and Hong Kong experience. International Journal of Behavioural Development, 14(4), 429-448.

- Hannas , W. C. (1997). Asia’s Orthographic Dilemma. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Ingulsrud , J. E. and Allen , K. (1999). Learning to Read in China: Sociolinguistic Perspectives on the Acquisition of Literacy. Lewiston, NY : E. Mellen.

- McBride-Chang, C., Chow, B. W.-Y., Zhong, Y., Burgess, S., and Hayward, W. G. (2005). Chinese character acquisition and visual skills in two Chinese scripts. Reading and Writing, 18(9), 99-128.

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel. Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction (NIH Publication No. 00-4769). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Liu, T.Y., and Hsiao, J. (2012). The perception of simplified and traditional Chinese characters in the eye of simplified and traditional Chinese readers. In N. Miyake , D. Peebles, and R. P. Cooper (Eds.), Proceedings of the 34th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society (pp. 689-694). Austin, TX: Cognitive Science Society.

Additional References:

- Lin, D., and McBride-Chang, C. (2010). Maternal mediation of writing and kindergartners’ literacy: A comparison between Hong Kong and Beijing. In Research in Reading Chinese (RRC) Conference.

- Lin, D., McBride-Chang, C., Aram, D., Levin, I., Cheung, R.Y.M., Chow, Y.Y.Y., and Tolchinsky, L. (2009). Maternal mediation of writing in Chinese children. Language and Cognitive Processes, 24(7-8), 1286-1311.

Tables:

Table 1: Compares the skills of college-attending adults’ in reading and writing Chinese in their less familiar script (taken from Liu & Hsiao, 2012, Table 1).(7)

Table 2: Compares the reading and visual skills of kindergarteners at two different time points (taken from McBride-Chang, et al., 2005, Table 1).(5)

**This piece was originally part of a series of posts. You can find the updated version, along with exclusive new chapters, in the ebook, (affiliate link) So You Want Your Kid to Learn Chinese. Special thanks to Mind Mannered for many of the references re: Traditional Chinese. I would not have been able to write much of this post without her diligent work and research. Thank you.

**A/N2: Also, Traditional vs Simplified Chinese is a highly sensitive topic for some so please be respectful. I will employ my commenting policy with a tyrannical hand both here and on my Facebook pages. I presume the admins will monitor the threads on the pages I do not “own.” Don’t be a dick. Also? I get to decide who’s being a dick. You’ve been warned. Behave.