Before I go any further, I want to point out what this post is NOT. This is not a post pitting pinyin against Zhuyin (Bopomofo).

I am not interested in some dogmatic discussion about how Zhuyin (Bopomofo) or pinyin is superior to the other. That is boring and stupid because it assumes that there can only be one thing that helps kids and adults learn Chinese. Life isn’t The Voice or American Idol. It is quite possible to have multiple good things simultaneously existing without resorting to which is “best.” Best for what, anyway?

What I actually want to do with this post is to make the case for why, if you want your kids to learn Chinese, in addition to having them learn pinyin, to also learn Zhuyin (Bopomofo).

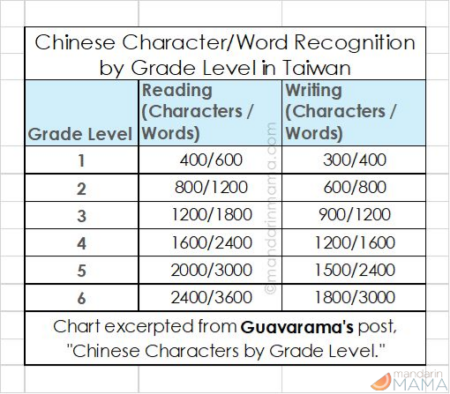

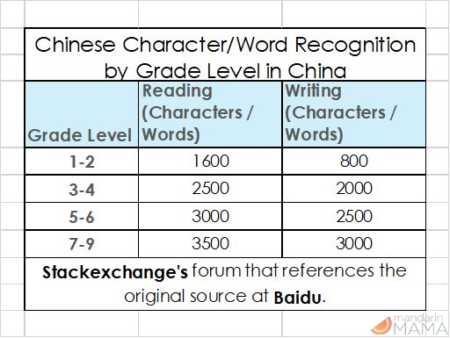

Also, this post pre-supposes you want your child to be literate in Chinese (be it Traditional or Simplified). And by literate, I mean actual literacy – not just recognize a few words here and there like 大小上下. For our purposes, by literate, I mean that your child should be able to read a newspaper with ease and recognize about 2,000-4,000 characters (at approximately Chinese 3rd or 4th-grade level and Taiwanese 6th-grade level). That is what both Mainland China as well as Taiwan consider “literate” and able to function in their societies. (I, personally, do not qualify as literate in this case. I am, on my best best best day, at about 800-1,000 characters.)

Incidentally, I could write a post focusing on a lower standard of literacy, but really, what would be the point? How would that even be remotely useful? (Sorry, this is totally a pet peeve of mine when people complain about my posts having standards that are too high. I digress.)

Anyhow, I actually think it is impractical not to know pinyin since it uses the romantic alphabet with which most English speakers are familiar. Also, it is especially useful for typing in Chinese since we are already used to typing using the American keyboard. I am much faster typing Chinese via my pinyin keyboard versus my Zhuyin (Bopomofo) or handwriting keyboard.

For adults and children who already know how to read English, they don’t have to learn a new “alphabet” and can almost immediately begin to try “reading” Chinese (albeit without comprehension) as long as there is pinyin next to Chinese characters. There is definitely a huge benefit to that!

Of course, this does prove problematic when it comes to proper pronunciation because if you already know how to read English (or any other language that uses the romantic alphabet), you are already used to another way of pronouncing those phonics. It is hard to get rid of that initial learning. Personally, I think the only reason I can pronounce things correctly with pinyin is that I already knew Zhuyin (Bopomofo).

But first, before I continue, for those who have zero knowledge: What the heck are pinyin and Zhuyin (Bopomofo) anyway? Lucky for you, I link to stuff on Wikipedia with abandon!

Pinyin – A standardized form of phonetics for transcribing Mandarin pronunciation of Chinese characters into the romantic alphabet. Used in Mainland China, Taiwan, and Singapore. Introduced in the 1950s. Replaced the old Wade-Giles Romanization.

Zhuyin (Bopomofo) – A standardized form of phonetic notation/symbols for transcribing Mandarin pronunciation of Chinese characters. Introduced in the 1910s in China and Taiwan although pinyin replaced Zhuyin in China whereas Taiwan still considers Zhuyin (Bopomofo) its official form of phonetic notation.

The history of Zhuyin is fascinating (and all the symbols are derived from “regularized” forms of ancient Chinese characters) and I highly recommend you read the Wikipedia article.

Okay, you might be thinking. That’s great that there is another phonetic notation out there to help kids read Chinese, but why would they need to learn an entirely different phonetic system if they already know pinyin? Isn’t that just redundant and adding an extra layer of unnecessary difficulty for your kids?

That’s a totally legitimate question and before I get to it, I want to point out a few things first.

One of the best ways to learn how to read and comprehend what you’re reading is to actually read. And to read a lot. (I know. It seems so obvious and unnecessary to point out, but nevertheless, I did.) So, for most children, their English reading (as well as Chinese reading) improves and gets better the more often and varied materials they read. It is especially helpful when kids find subjects and stories they love because then reading is fun, engaging, and interesting.

For English readers, this is not really a problem because once children learn phonics, they can pretty much read anything as long as they can blend the sounds. The limiting factor for children reading in English (whether a native speaker or not) is then a matter of comprehension.

However, Chinese is NOT a phonetic language. Written Chinese is logosyllabic (ie: each syllable is represented by a character) and there are upwards of 20,000-40,000 unique characters – of which you require about 2,000-4,000 to be considered functionally literate. A word can be either a single character (eg: 大 /big) or a combination of characters (eg: 眼睛/eye).

Here’s the sad truth: If your child understands more Chinese than they can read, the limiting factor for them reading Chinese books is character recognition.

Furthermore, if your child is not a native speaker and doesn’t have much additional language support, they will be severely limited by both comprehension as well as character recognition.

Chinese literacy will be difficult. I cannot overstate that fact.

Consider also, the fact that millions of American Born Chinese (as well as Brought Over By Airplane) people can speak and understand Chinese and yet, even for them, they can perhaps barely read a menu. (And only because food is an incredibly motivating factor.)

Here are some more sobering facts for you:

Sources: Guavarama

Sources: Stackexchange and Baidu

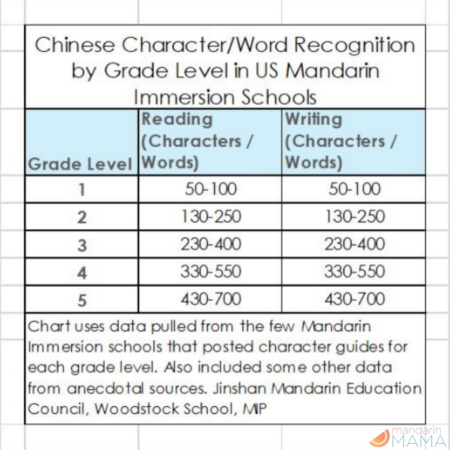

Sources: Jinshan Mandarin Education Council, Woodstock School, and MIP

Unfortunately, if your child already knows how to read English, it is highly improbable that their Chinese recognition is advanced enough for them to read at the same level (in subject matter, depth, and difficulty) as they can already read in English. (Incidentally, because they already understand and have applied the concepts of phonics and blending, they should pick up Zhuyin really easily.)

Consider Zhuyin Sample 1, an excerpt from a children’s book (click to embiggen). My almost six-year-old son, Cookie Monster, can read about 400-500 characters but still can’t read ALL of these characters on this page. He can read most of them – but definitely not ALL. So, even though he knows about 15% of the High-Frequency Words, he still cannot read a children’s book.

If you’re paying attention, you’ll notice that Cookie Monster is at about the 3rd-5th grade level in US Mandarin Immersion schools. If you think a 3rd-5th grader will find this book interesting beyond possibly five minutes (if even that), I would daresay you should reconsider.

Now, Cookie Monster is turning six in a few weeks and cannot read English (something I have chosen to do purposefully). But if he could read English, likely he would be able to read a comparable children’s story in English with great ease. And if he were used to that level of reading and comprehension, the fact that he could not read all the words in this “baby” book would be incredibly frustrating.

I have many friends whose kids, at six and a half, are already reading chapter books in English. There is NO WAY they could read chapter books in Chinese (and these are kids in 90/10 Mandarin Immersion schools).

As a result, the Chinese books they can read are too “babyish” for them and they lose interest either due to the dull subject matter or because the stuff they would actually be interested in reading is too hard so they give up.

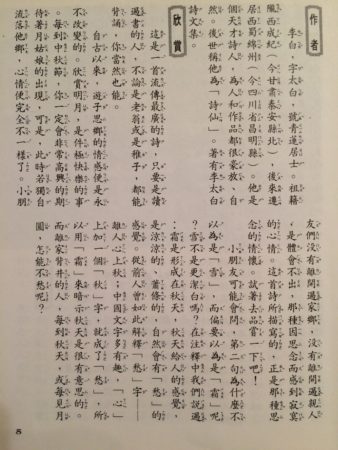

Zhuyin Sample 2: The explanation of a Tang classical poem, 靜夜思(A Quiet Night Thought) by 李白 (Li Bai)

Zhuyin offers your child a way to read the materials they want at the level they want without character recognition being a hurdle.

Because Zhuyin is phonetic, it is a fantastic tool for “leveling” the reading field, as it were. As you can see from the pictures (click to embiggen), Zhuyin is usually placed to the right of Chinese characters so children can read the characters they know and if they happen upon a character they don’t know, they can just look at the Zhuyin to read the phonetic notation and they will be able to continue through the story with no problem. The only limit, again, being their understanding/comprehension (as it would be in English).

Zhuyin Sample 2 is an excerpt from a Chinese Tang poetry book I owned when I was a child. This particular page is explaining the meaning of the classical poem, 靜夜思(A Quiet Night Thought) by 李白 (Li Bai). Now, even though I can read perhaps at best, 800-1,000 characters, I can read every single word in this sample because of the Zhuyin (Bopomofo). Now, whether I comprehend these words is a different story, but I am not hindered from reading and learning from the text by my limited vocabulary.

Thus, a child, if they were interested in Chinese Tang poetry, could read and potentially understand this subject matter. (Truthfully, I think that if it were the same type of text explaining a Shakespearean sonnet in English, the comprehension level would likely be about the same).

Now, I don’t know too many kids interested in classical Chinese poetry – but surely, you can extrapolate and come up with some books a 3rd, 4th, or 5th grader might be interested in reading – and THOSE could be in Zhuyin(Bopomofo).

My point is that now, the primary obstacle (character recognition) to your child reading in Chinese has now been removed. English and Chinese reading are both now on a more “level” playing field. Of course, if your child is not a native speaker of Chinese, (and even if they are), most likely because we live in an English speaking country, your child’s English comprehension will still surpass their Chinese comprehension.

But as I mentioned earlier, the more your child reads (in both quantity and variety), the more your child will understand.

Well, I can hear you thinking. Why not just get books in both pinyin and Chinese? And what about kids in China? Don’t they use pinyin and their pronunciation is just fine?

Great questions.

To the first, in China, my understanding is that only textbooks use pinyin with Chinese characters – and even then, only for young children. There is a reason children in Mainland China learn Chinese characters at a higher rate than kids in Taiwan. They need to amp up their character recognition in order to read the books at their intersecting comprehension and interest levels.

In Taiwan, Zhuyin is only phased out at the 3rd-4th-grade level so children can afford to learn Chinese characters at a slower rate than their Mainland Chinese counterparts. As a result, the majority of children’s literature will also have Zhuyin so kids can enjoy many types of books without being limited by their lesser character recognition.

For kids in English speaking countries, there is a reason Immersion schools delay the teaching of pinyin until their students have already mastered reading in English. Otherwise, it is too easy for kids to confuse the “different” sounds each letter symbolizes in English and pinyin. When they finally do learn pinyin, their pronunciation of Chinese often suffers because it is much easier to “slip” into the English instead of the Chinese letter pronunciation.

As for why kids in China aren’t affected by pinyin pronunciations, I should think it’s obvious: they’re Chinese. They live in China. Where the official language is Mandarin Chinese. They already speak and understand Chinese (just like an American kid already speaks and understands English). I think it would be a little ridiculous to expect the Chinese people to have trouble pronouncing their own language.

When kids in China use pinyin, they are literally using it in the same manner kids in Taiwan are using Zhuyin (Bopomofo). But since they learn so many more characters at a lower grade level, there is less of a need to have books with pinyin in them. (Plus, there is a little problematic matter of formatting. Fitting Chinese characters to pinyin makes for very awkward formatting issues in books. Can you imagine how bulky a chapter book would be?)

However, since Taiwanese kids are still using Zhuyin up to about 3rd or 4th grade, there are lots and lots of books (both chapter and non, fiction or non-fiction) with Zhuyin. (I recall that in 5th grade, I read Little Women in Chinese first – and all due to the presence of Zhuyin. So to this day, I still think of the four women’s character names in Chinese first.)

As a side benefit, because the books have more complicated characters with Zhuyin, it also helps children with literacy and recognizing harder characters. They have already encountered them in their books and subject matter so when they finally learn the actual character without Zhuyin, the kids have already been exposed enough so that it is relatively easier to remember.

Plus, now it doesn’t matter as much whether the characters are in Traditional or Simplified because regardless, as long as there is Zhuyin, the kids can read the characters. In full disclosure, this is a bit of a false benefit since Zhuyin (Bopomofo) is pretty much only used with Traditional characters since it is used primarily in Taiwan. So, it doesn’t really help kids who only know Traditional characters with Simplified.

However, it does open up a huge section of books to kids who only know Simplified (and honestly, Traditional, too) because as I mentioned, as long as they can read the Zhuyin, character recognition is no longer the problem. (I wouldn’t be surprised then if kids also picked up Traditional characters, too. Another win!)

Another ancillary benefit of learning Zhuyin (Bopomofo) is that since Zhuyin was created from ancient forms of Chinese characters, lots of them show up as components in the actual Chinese characters (as well as look like the sound they make). This helps children recognize and remember the parts and components of more complicated characters. (My post last week discusses a little more in-depth how characters are formed, as well as Traditional and Simplified characters.)

I know that Cookie Monster and Gamera, as well as Guava Rama’s son, Astroboy, all point out the different Zhuyin, smaller characters, and radicals they see as components in a word. These visual cues definitely help the children remember what a character looks like, sounds like, and means. (My guess is that this may prove more useful with Traditional characters since many Simplified characters might have elided these components.)

For example (for clarity, I’m only including the components that look like Zhuyin):

– An ㄠ and ㄏ in 麼

– 3 ㄑin 輕

– An ㄦ in 兒

– A ㄙ in 台

Now, obviously, kids can find other visual cues without knowing Zhuyin – so by no means is it conferring a benefit the kids wouldn’t otherwise have. However, it is just an extra tool (actually, an extra 37 tools) the kids can use to help with recognizing Chinese characters – and as we have already established, Chinese is a difficult language to read and our kids need all the help they can get.

So, in summary, here are the main reasons why I think you should consider teaching your kids Zhuyin (Bopomofo) in addition to pinyin:

1) Removes the considerable barrier of character recognition from reading age/interest appropriate materials. This leaves only the problem of Chinese comprehension which can easily be ameliorated by more reading practice (as well as listening and conversation which usually are well ahead of reading comprehension in English as well).

2) Opens up a vast selection of age/interest appropriate materials from Taiwan because character recognition is no longer an issue. This way, even if your child has only learned Simplified characters thus far if they know Zhuyin, they can also read (and perhaps learn) Traditional.

3) Improves pronunciation and tones because the symbols more accurately reflect those sounds. (Again, I realize that though the symbols may convert to roman letters, we as native English speakers, have a harder time “switching” pronunciation and can either slip or get lazy. Whatever the reason, the temptation to “read” the pinyin with English pronunciations is high.)

4) Increases character recognition of more complex characters due to exposure.

5) Adds an additional visual cue for children to help remember more complex and compounded characters.

6) If your child can already read English and understands the concept of blending and phonics, they will learn Zhuyin quickly and easily. If they cannot already read English, this will introduce these concepts and make learning to read English easier.

7) Adds more tools in your children’s Chinese Toolkit in the sense that Zhuyin (Bopomofo) is an alternate way to type on keyboards, look up words in dictionaries (sometimes, I just cannot figure out the pinyin of a word for the life of me and I just end up resorting to Zhuyin and I find it in second), and substitute for unknown characters when writing (although I suppose technically, they can do that with pinyin, too).

8) Adds a “sound” cue for children. (h/t Guava Rama)

– ㄦ(er) in 兒 (er): sounds like the Zhuyin

– ㄅ(be) in 包 (bao): starts with the ㄅ Zhuyin sound

Alright folks. As always, I am incapable of writing anything in brief. Thanks for sticking it through.

I sincerely hope you consider adding Zhuyin to your children’s Chinese Toolkit. Most Mandarin Immersion elementary schools expect their kids to graduate at 5th grade with about 600-800 characters. That is only 20-27% of the High-Frequency Words your children will need in order to be actually literate.

If that is fine with you, wonderful!

I am at approximately that level and except for when I’m in Taiwan or China, that has rarely ever prevented me from living a full and wonderful life in the US. (And even when I have been in Taiwan or China, the pain was relatively minor. Mostly my ego and being illiterate in a country where I look like the people there and the shame I feel – well, that’s a temporary and small thing.)

However, if you would like to increase your child’s Chinese literacy to be functional in Chinese/Taiwanese society, Zhuyin will help you reach that goal with greater facility.

Thanks so much for reading! Have a great weekend.

Other resources:

1) Zhuyin Table – a complete listing of all Zhuyin/Bopomofo syllables used in Standard Chinese

2) A great Zhuyin/Pinyin conversion chart from Little Dynasty. (I don’t know how printable it is, but it’s the prettiest table I found.)

3) Miss Panda also has a great printable Zhuyin/Pinyin Conversion Table.

**This piece was originally part of a series of posts. You can find the updated version, along with exclusive new chapters, in the ebook, (affiliate link) So You Want Your Kid to Learn Chinese.